Gareth Tribello - MathNet - Classical Thermodynamics

Notes on MathNet

This is a multi-part post:

The analogy between classical Thermodynamics and Newtonian Mechanics

- In absence of external stimulus, volume, temperature, and number of atoms don’t change. These are called thermodynamic variables, and are of two types:

- Extensive variables - value depends on the number of atoms, e.g. number of atoms, volume

- Intensive variables - value does not depend on the number of atoms, e.g. temperature, pressure

- Thermodynamic law equivalent to Newton’s first law: Any physical system remains in equilibrium with extensive thermodynamic variables fixed unless acted upon by an external agent

- In Newtonian mechanics, to change a system, you must change its momentum, and you do so by applying a force \(F = \frac{\mathrm{d}p}{\mathrm{d}t}\)

- In classical thermodynamics, the state of a system is characterized by many extensive thermodynamic variables.

- To change the state of the system, you can act to change any of these extensive variables

- For example, by changing its volume. Or its temperature.

- We need to quantify how a change in one extensive variable impacts other extensive variables.

- A phase is a part of space.

- Can divide a system in Phase 1, with number of atoms \(N_1\), volume \(V_1\) and pressure \(P_1\), and Phase 2, with number of atoms \(N_2\), volume \(V_2\), and pressure \(P_2\).

- The extensive variables of Phase 1 will change when put in contact with a second phase Phase 2 which has different values for its extensive variables.

- Assume \(P_1 \gt P_2\).

- Then \(V_1\) will increase, and \(V_2\) will decrease, b/c the total volume is constant.

- The pressure \(P_1\) will decrease. The pressure \(P_2\) will increase.

- The changes will stop when the two pressures are equal.

- At equilibrium, the intensive variables take a single value across the entire system

- Thermodynamic laws:

- Behavior in absence of an external agent: Thermodynamic system remains in equilibrium, with values of extensive variables unchanged.

- How external agent couples to system: If two phases are put in contact, then the values of conjugate extensive variables will change.

- Conservation principle: When two phases come to equilibrium, then any incraese in the values of extensive variables in one system must be compensated by a decrease in second phase.

- Origin of thermodynamics: scientists wanted to understand how engines work

Temperature and the Gibbs Phase rule

- We can characterize the state of a system phase by denoting the values of all extensive thermodynamic variables within it.

- If a phase is put in contact with a 2nd phase, with different intensive thermodynamic variables, then the state of the phase will change.

- For example, if a force is applied to a lump of material, then its volume could change.

- This action is quantified throug intensive thermodynamic variables.

- Idea underemphasized in thermodynamics textbooks: temperature is an intensive thermodynamic variable

- The fact that temperature is an intensive thermodynamic variable is evident by the way we measure temperature with a thermometer.

- Volume of mercury in tube changes. Volume is an extensive thermodynamic variable.

- The fact that temperature is an intensive thermodynamic variable is evident by the way we measure temperature with a thermometer.

- A phase is basically a part of the sapce. We choose it arbitrarily.

- Given Phase1, Phase2

- With extensive variables \(V_1, V_2\) (volume)

- With intensive variables \(P_1, P_2\) (pressure)

- If the intensive variables \(P1 = P_2\), these two phases are in equilibrium, and the values of the extensive variables \(V_1, V_2\) will not change.

- If \(P_1 \gt P_2\), then Phase 1 will expand, and its volume will increase, while that of Phase 2 will contract.

- Vice-versa, if \(V_1\) increases and \(V_2\) decreases, then \(P_1\) decreases and \(P_2\) increases. This process continues until the pressures become equal, at which point the system is in equilibrium.

- Consider this process with temperature

- Temperature is intensive. Any difference in temperature will drive changes in the states.

- Suppose the volumes of the two phases are fixed throughout, and atoms are not allowed to move between phases.

- If \(T_1 /gt T_2\), then how will the system change?

- Answer: we introduce a new extensive variable: the entropy \(S_1, S_2\).

- Entropy describes how two systems with set number of atoms and volume can come to an equilibrium when temperature changes.

- As \(T_1\) decreases, and \(T_2\) increases, in order to bring temperature to equality, the entropy \(S_1\) decreases, and \(S_2\) increases.

- You might have heard bullshit in other places that entropy is related to disorder. Yuck! Aside from being wrong, this is an incomprehensible statement.

- How is it related to disorder? What does that even mean?

- Alternatively, entropy is sometimes described as the quality of energy. That’s equally wrong.

- Please forget all this crap now! For the time being, define entropy as follows:

- Entropy is the conjugate extensive variable to the intensive variable temperature

- We are then going to developed a more refined description of entropy as we go along.

- It does not involve any nonsense like disorder or quality of energy

- What does it mean for entropy to be a conjugate extensive variable to temperature?

- It means that temperature is to entropy as pressure is to volume.

- What we mean by conjugate is that if we change pressure, and do not allow change in entropy or number of atoms, the phases will come to equilibrium by changing their volume.

- Hence, two phases with different temperature, which are not allowed to change volume or number of atoms, will come to equilibrium by changing this mysterious extensive variable called entropy.

- Consider phases that can change matter between them

- Extensive variables are the number of atoms \(N_1, N_2\)

- Assume \(N_1\) decreases, and \(N_2\) increases

- The conjugate intensive variable to the number of atoms is another made-up intensive variable: the chemical potential \(\mu_1, \mu_2\)

- The flow of matter from Phase 1 to Phase 2 is given by a difference in the chemical potential \(\mu_1 \gt \mu_2\)

- The chemical potential \(\mu_1\) decreases, and \(\mu_2\) increases.

- This process continues until the chemical potential becomes equal.

- Each intensive variable must have a conjugate extensive variable

- We thus introduce entropy and chemical potential

- This is the easiest way to introduce these thermodynamic variables.

- They are created for mathematical convenience only - unline quantities such as pressure, volume, number of atoms.

- It is not easy to explain what these thermodynamic variables physically represent.

- Given Phase1, Phase2

- The state of one phase is completely characterized by a small set of thermodynamic variables.

- Two phases at equilibrium must have the same values for all intensive thermodynamic variables

- We will prove in these lectures the Gibbs phase rule: \(F = C - \pi + 2\), where \(F\) is the number of independent thermodynamic variables, \(C\) is the umber of chemical components (molecule types), \(\pi\) is the number of phases.

- Consequence: All thermodynamic variables can be calculated if we are given a subset of the thermodynamic variables - for example, at equilibrium, we can write an equation for the pressure in terms of volume and temperature.

The efficiency of the Carnot engine

- What is temperature?

- Can’t characterize it as what’s hot, because we don’t know what hot means, without defining hot in terms of temperature

- Can’t be a characteristic of the system, because the system is characterized by extensive thermodynamic variables, whereas temperature is intensive.

- 19th Century physicists sorted this out.

- They were interested in how steam engines worked.

- In these engines, gas was heated or cooled down, and pistons were used to do work in the environment

- Because of Newton’s third law - every action has an equal and opposite reaction - work had to be transferred on the environment.

- It should be able to calculate exactly the work done by the piston by integrating over the change in volume.

- Physical idea: add something hot to something cold, and the cold thing would get hotter (and the hotter system colder). But I would never see the opposite process.

- No process is possible in which the sole result is the transfer of heat from a colder to a hotter body.

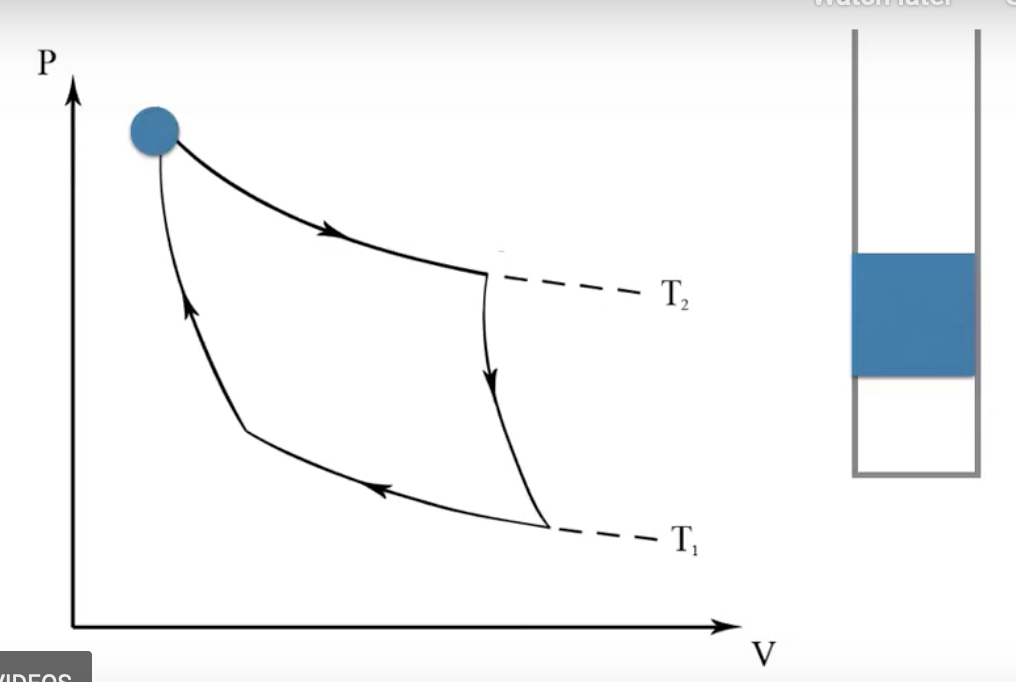

- Introducing the reversibe Carnot engine.

- The gas inside the engine is a one component system. When it’s at equilibrium, its state should be characterized by \(1-1+2=2\) thermodynamic variables.

- If we have the pressure and the volume of the gas in the cylinder, and if the gas in the engine is at equilibrium, we should be able to reconstitute the state of the gas in the engine.

- On completing a full cycle in the Carnot loop, we will return at the initial thermodynamic state of the gas in the engine.

- Consider each of the four steps

- In the 1st step, the engine is put in contact to a heat bath, and is allowed to expand

- Gas in the engine stays at the same temperature \(T_2\)

- Heat flows from the bath into the gas

- Gas expands isotthermally.

- In the 2nd step - remove the heat bath. Thermally lag the system. No heat is transferred. When the gas expands further, the temperature decreases to \(T_1\). Adiabatic expansion - adiabatic because heat is not allowed to transfer in the environment.

- In the 3rd step, we remove the thermal lag and put the system in contact with a heat sync. Temperature stays at \(T_1\). The gas contracts, and heat flows from the system into the sink. The gas and the system are contracting isothermally.

- In the 4th step, we remove the heat sync, and introduce the thermal lagging once more. The system is not allowed to transfer heat to its environmet. The gas in the cylinder is further contracted. Adiabatic contraction.

- In the 1st step, the engine is put in contact to a heat bath, and is allowed to expand

- When gas is expanded, in steps 1 and 2, work is done on the universe: \(-w_2\)

- When gas is contracted, in steps 3 and 4, work is done by the universe on the system: \(w_1\).

- Total work done by the gas is \(-\Delta w = w_2 - w_1 \gt 0\). It is greater than \(0\) because we want the engine to do work on the universe, else it would be a useless engine.

- \(q_H\) heat transferred from universe to engine in 1st step, \(q_C\) heat transferred from engine to universe in 3rd step

- Will have \(q_H - q_C = \Delta w\)

- The left side is the efficiency of the engine - the ratio of work done to heat input.

- Will now show there is no engine more efficient Carnot engine going from the same temperature \(T_2\) to \(T_1\).

- A new engine would use less heat for the same amount of work: \(q_H^{\prime} \lt q_H\)

- We must also have \(q_C^{\prime} \lt q_C\)

- Run the new Carnot engine forward, and the original Carnot engine in reverse.

- Then, we would do zero total work.

- And we would get \(q^{\prime}_H - q_H \lt 0\) from the hot sink, and give \(q^{\prime}_C - q_C \lt 0\) to the cold sink

- This would make the hot sink hotter, and the cold sink colder with zero work - contradiction

The Kelvin definition of temperature

- We can use the Carnot engine to create a universal calibration for temperature

- 1st step is to assert that a function \(g(T_1, T_2)\) exists that allows us to calculate the efficiency of the Carnot engine

- Define \(f(T_1, T_2) = 1 - g(T_1, T_2) = \frac{q_C}{q_H}\)

- Denote heat exchanged as \(q_1, q_2, q_3\).

- So $f(T_1, T_2) = \frac{q_1}{q_2}$$, etc

- We get \(f(T_1, T_3) = f(T_1, T_2) f(T_2, T_3)\)

- This means \(f(T_1, T_2)\) can be written as a quotient of a new function \(f(T_1, T_2) = \frac{F(T_1)}{F(T_2)}\)

- The simplest function we can choose for \(F\) is the identity function \(F(T)=T\)

- This is the basis of the Kelvin scale:

- The Carnot efficiency can be rewritten as:

- When \(T_C = 0\), the Carnot efficiency becomes \(1\).

During adiabatic expansion:

\[\begin{align*} \Delta w = - \int_x^{x+\Delta x} F \mathrm{d}x = - \int_x^{x+\Delta x} pA \mathrm{d}x = - \int_V^{V+\Delta V} p \mathrm{d}V \end{align*}\]where the force \(F\) is pressure \(p\) times piston area \(A\), and volume \(V\) is area times height \(Ax\).

- We’ve characterized the state of the Carnot cycle in terms of pressure and volume.

- Work done during the adiabatic transition:

- Can we derive a similar formula for the heat exchanged during the isothermal transition?

- \(q\) is the amount of heat that flows during a transition.

- We’ll argue that we can compute \(q\) by integrating temperature over entropy as follows:

- Suppose the transition is isothermal. Then:

- Since \(\frac{q_1}{T_1}=\frac{q_2}{T_2}\), we get \(\Delta S_1 = \Delta S_2\)

- The total change in entropy going around the Carnot cycle is \(0\).

- The entropy of an equilibrium state is a property of that state. It does not depend on how the state was prepared.

- The state of a system is characterized by its extensive thermodynamic variables

- The actions on the environment of that system are chanracterized by its intensive thermodynamic variables.

- The state of a one-phase system is characterized by its volume and its entropy.

The first law of thermodynamics, handout

- Recollection of intensive vs extensive thermodynamic variables.

- Work done during the adiabatic transition:

- No heat exchanged in this step. Entropy remains constant.

- Transfer of heat during isocoric transition, when volume is constant, and only entropy changes:

- Will characterize system when state changes both volume and entropy

- We introduce the internal energy:

- If our transition is adiabatic - and entropy is fixed - then the change in internal energy is the work done on the system.

- If the transition is isocoric, the change in internal energy is the exchange of heat.

- Integration is reverse of differentiation, so:

- First law of thermodynamics: The internal energy is a function of state.

- The change in energy depends only on the first and last point

- In the Carnot cycle, we already saw that \(q_h - q_c - \Delta w = 0\). This is another form of the first law of thermodynamics.

The second law of thermodynamics

- In the Carnot cycle, \(\Delta E = q_h - q_c - \Delta w = 0\).

- All the heat from the hot source is transferred to work and to the cold source. None of the heat is lost.

- In real engines, this will be not likely the case. Energy is lost in friction, etc.

- For real engines, we get \(\Delta E = q_h - q_c - \Delta w > 0\), or

- This tells us the Carnot engine is the most efficient engine there is.

- Sub in the Kelvin definition of temperature.

- If the imperfect engine exchanges heat between \(q_h^\prime, q_c^\prime\), between the same temperatures, then it needs to have

- We get rid of primes

- We rephrase:

- Can write it as a path integral around the cycle:

- This is the Clausius inequality

- On a conserving energy path from \(B\) to \(A\), we can replace \(\mathrm{d}q\) by \(T\mathrm{d}S\), and we have:

- On a non-conserving energy path from \(A\) to \(B\), by the Clausius inequality, we get the 2nd law of thermodynamics:

- For an isolated system, \(\mathrm{d}q = 0\), and \(\Delta_{A \rightarrow B} S \ge 0\)

- The entropy of an isolated system increases during a spontaneous change

Combining the first and second laws of thermodynamics

- \[\mathrm{d}E = \mathrm{d}w + \mathrm{d}q\]

- Here \(\mathrm{d}w, \mathrm{d}q\) should be usually denoted with a small bar cut over d to denote the fact that the work \(w\) and the heat \(q\) are not function of state. The forms \(\mathrm{d}w, \mathrm{d}q\) are not exact. The work done on the system \(\int \mathrm{d}w\) and the heat absorbed \(\int \mathrm{d}q\) will depend on the path between states.

- Representing the states in volume and entropy coordinates, we get

- This is another way to say that:

- The change in internal energy of the system when one of the extensive variables changes, and all other extensive variables are constant, is

- Here \(I\) is an intensive thermodynamic variable, and \(E\) is an extensive thermodynamic variables.

- For example, \(I\) could be the chemical potential \(\mu\), and \(E\) could be its conjugate extensive thermodynamic variable, the number of atoms \(N\).

- We can use the same mathematical description to formulate the effect that the electric and magnetic field have on the system, and so forth.

- Extensive variables are function of state.

-

Intensive variables are related to partial derivatives of internal energy with respect to their conjugate extensive thermodynamic variable \(\begin{align*} T &= \left(\frac{\partial E}{\partial S} \right)_V \text{ where V=extensive, P=conjugate intensive} \\ P &= - \left(\frac{\partial E}{\partial V} \right)_S \text{ where S=extensive, T=conjugate intensive} \\ \mu &= - \left(\frac{\partial E}{\partial N} \right) \text{ where N=extensive,} \mu \text{=conjugate intensive} \\ H &= - \left(\frac{\partial E}{\partial M} \right) \text{ where magnetisation M=extensive, magnetic field strength H=conjugate intensive} \\ \end{align*}\)

- Why are the values of intensive thermodynamic variables uniform throughout the system at equilibrium?

- Assume an isolated system, with two phases, separated by a diathermal wall, that allows heat to be exchanged, but not matter or work.

- The volume would not be allowed to change. The entropy would.

- If temperature of phase 1 is higher than of phase 2, entropy would be transferred from phase 1 to phase 2.

- The change in total energy is \(\mathrm{d}E = T_1 \mathrm{d}S_1 + T_2 \mathrm{d} S_2\)

- The system is isolated, so \(\mathrm{d}E=0\)

- At equilibrium, we also have \(\mathrm{d}S_2 = -\mathrm{d}S_1\)

- So \(T_1=T_2\) at equilibrium

- If two phases can exchange some quantity, then they must assume a common value for the conjugate intensive quantity

- This is a consequence of the 1st and 2nd laws of thermodynamics

- The Gibbs phase rule is a consequence of this equality in the values of intensive variables

- The minimum energy compatible with a value of entropy is in an equivalent state to when the maximum entropy for a given value of energy.

From the handout, actually

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{d}E = \frac{\partial E}{\partial S}_{V,N} \mathrm{d}S + \frac{\partial E}{\partial V}_{S,N} \mathrm{d}V + \frac{\partial E}{\partial N}_{V,S} \mathrm{d}N \\ \end{align*}\]and identifying the partial derivatives with respect to intensive thermodynamic variables with the corresponding conjugate thermodynamic variable:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{d}E = T\mathrm{d}S - P\mathrm{d}V + \mu \mathrm{d}N \\ \end{align*}\]The partial derivatives commute, so:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial T}{\partial V}_{S,N} = - \frac{\partial P}{\partial S}_{V,N} \end{align*}\]- Ethalpy \(H=E + PV\)

- When the system is in contact with an infinite reservoir, expanding the system volume does \(\mathrm{d}(PV)\) work on the reservoir

- If the reservoir is infinite, we would lose the effect of this work.

- To not lose the effect, keep track of changes in energy not as \(\mathrm{d}E\) but as \(\mathrm{d}E+\mathrm{d}(PV) = \mathrm{d}E+P\mathrm{d}V+V\mathrm{d}P\)

- But \(\mathrm{d}E=T\mathrm{d}S-P\mathrm{d}V\) so we’re keeping track of \(T\mathrm{d}S+V\mathrm{d}P\)

- This sum is the change in a new thermodynamic potential called Enthalpy \(H = E + PV\)

- \[\mathrm{d}H = T \mathrm{d}S + V \mathrm{d}P\]

- Enthalpy, like energy, entropy, volume is a fuction of state.

- The change in ethalpy between two states does not depend on the path taken.

- We can also write \(\mathrm{d}H = \frac{\partial H}{\partial S} \mathrm{d}S + \frac{\partial H}{\partial P} \mathrm{d}P\)

- We can thus identify \(\frac{\partial H}{\partial S} = T\) and \(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}=V\)

- Helmholtz free energy \(F\)

- Consider a reservoir whose volume does not change when the system expands/contracts, but which stays at constant temperature so as to assure that it is unaffected when entropy is exchanged between the system and the environment

- We assume that the entropy of the reservoir is infinite

- Assume heat is exchanged with the reservoir.

- Normally, reservoir would absorb \(-T\mathrm{d}S\) of heat

- We will develop a thermodynamic potential which characterizes the amount of work/heat exchanged

- We must keep track of this extra energy that would normally be absorbed by the reservoir.

- We consider the infinitesimal \(\mathrm{d}E - \mathrm{d}(TS)\).

- The 2nd term would normally be the heat absorbed by the reservoir as its entropy increases and as the system’s entropy decreases.

- We get \(\mathrm{d}E - \mathrm{d}(TS) = \mathrm{d}E - T\mathrm{d}S - S\mathrm{d}T = -P \mathrm{d}V - S \mathrm{d}T\)

- Define \(F=E-TS\).

- We get \(\mathrm{d}F=-P \mathrm{d}V - S \mathrm{d}T\)

- We get \(-P = \frac{\partial F}{\partial V}\) and \(-S = \frac{\partial F}{\partial T}\)

- This finally gives a way to compute the entropy \(S\)

- Other termodynamic potentials have similar formal properties

- Gibbs free energy \(G=H-TS\)

- Grand potential (constant volume) \(\Omega = F - \mu N\)

- Repeat of the previous

Response function in classical thermodynamics

- Defines response functions

- Shows from the 1st and 2nd laws of thermodynamics that we can deduce formally other basic physical observations, for example, that heat flows from warmer systems to colder systems.